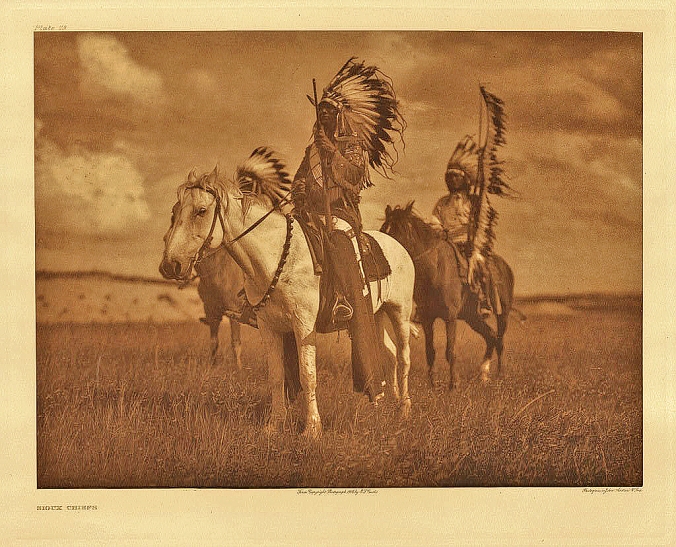

From my own copies of the Roycrofter Press issues from 1900

The earliest 20th-century exposé on love and relationships between men and women. One of the most insightful essays you will ever read.

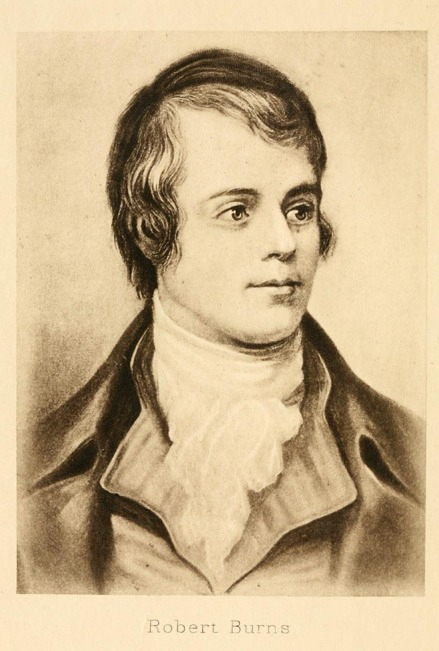

Robert Burns by Elbert Hubbard

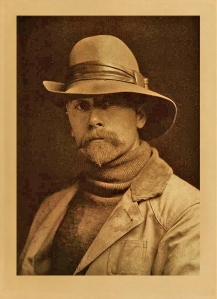

Elbert Hubbard In “Little Journeys to the Homes of English Authors.”

TO JEANNIE

Come, let me take thee to my breast,

And pledge we ne’er shall sunder;

And I shall spurn, as vilest dust,

The warld’s wealth and grandeur.

And do I hear my Jeannie own

That equal transports move her?

I ask for dearest life, alone,

That I may live to love her.

Thus in my arms, wi’ a’ thy charms,

I clasp my countless treasure;

I’ll seek nae mair o’ heaven to share

Than sic a moment’s pleasure.

And by thy een, sae bonnie blue,

I swear I’m thine for ever:

And on thy lips I seal my vow,

And break it shall I never.

—Robert Burns

The business of Robert Burns was love-making. All love is good, but some kinds of love are better than others. Through Burns’ penchant for falling in love we have his songs.

A Burns bibliography is simply a record of his love-affairs, and the spasms of repentance that followed his lapses are made manifest in religious verse.

Poetry is the very earliest form of literature, and is the natural expression of a person in love; and I suppose we might as well admit the fact at once that without love there would be no poetry.

Poetry is the bill and coo of sex. All poets are lovers, and all lovers, either actual or potential, are poets. Potential poets are the people who read poetry; and so without lovers the poet would never have a market for his wares.

If you have ceased to be moved by religious emotion; if your spirit is no longer exalted by music, and you do not linger over certain lines of poetry, it is because the love-instinct in your heart has withered to ashes of roses. It is idle to imagine Bobby Burns as a staid member of the Kirk; had he been so, there would now be no Bobby Burns. The literary ebullition of Robert Burns (he himself has told us) began shortly after he had reached the age of indiscretion; and the occasion was his being paired in the hayfield, according to the Scottish custom, with a bonnie lassie. This custom of pairing still endures, and is what the students of sociology call an expeditious move. The Scotch are great economists—the greatest in the world. Adam Smith, the father of the science of economics, was a Scotchman; and Draper, author of “A History of Civilization,” flatly declares that Adam Smith’s “Wealth of Nations” has influenced the people of Earth for good more than any other book ever written—save none.

The Scotch are great conservators of energy.

But they all make hay while the sun shines, and count it joy. Liberties are allowed during haying-time that otherwise would be declared scandalous; during haying-time the Kirk waives her censor’s right, and priest and people mingle joyously. Wives are not jealous during hay-harvest, and husbands never faultfinding, because they each get even by allowing a mutual license. In Scotland during haying-time every married man works alongside of some other man’s wife. To the psychologist it is somewhat curious how the desire for propriety is overridden by a stronger desire—the desire for the shilling. The Scotch farmer says, “Anything to get the hay in”—and by loosening a bit the strict bands of social custom, the hay is harvested.

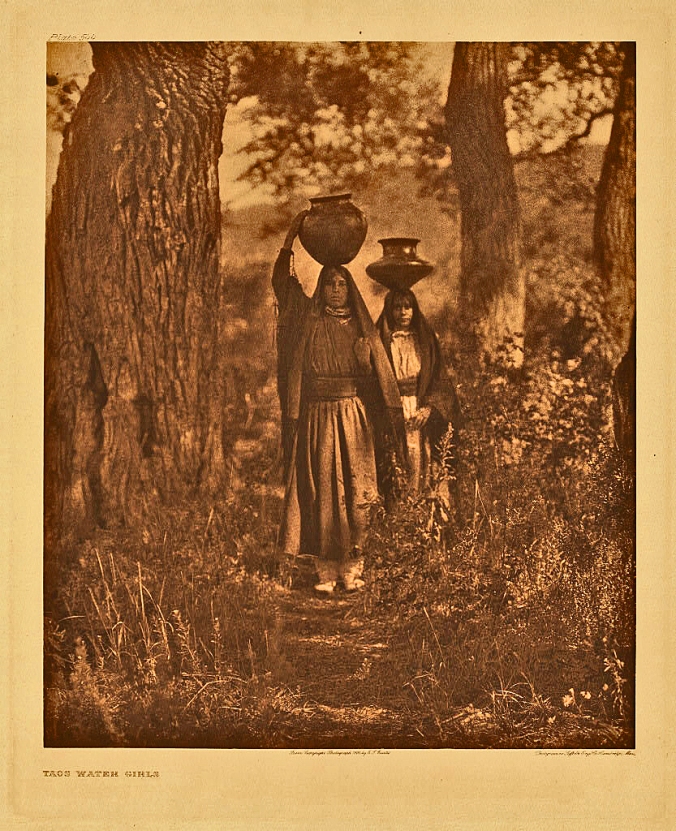

In the hay-harvest the law of natural selection holds; partners are often arranged for weeks in advance; and trysts continue year after year. Old lovers meet, touch hands in friendly scuffle for a fork, drink from the same jug, recline at noon and eat lunch in the shade of a friendly stack, and talk to heart’s content, sweetening the labor of the long summer day.

Of course this joyousness of the haying-time is not wholly monopolized by the Scotch. Haven’t you seen the jolly haying parties in Southern Germany, France, Switzerland and the Tyrol? How the bright costumes of the men and the jaunty attire of the women gleam in the glad sunshine!

But the practise of pairing is carried to a degree of perfection in Scotland that I have not noticed elsewhere. Surely it is a great economic scheme! It is like that invention of a Connecticut man, which utilizes the ebb and flow of the ocean-tides to turn a gristmill.

And it seems queer that no one has ever attempted to utilize the waste of dynamic force involved in the maintenance of the Company Sofa.

In Ayrshire, I have started out with a haying party of twenty—ten men and ten women—at six o’clock in the morning and worked until six at night. I never worked so hard, nor did so much. All day long there was a fire of jokes and jolly gibes, interspersed with song, while beneath all ran a gentle hum of confidential interchange of thought. The man who owned the field was there to direct our efforts and urge us on in well-doing by merry raillery, threat, and joyous rivalry.

The point I make is this—we did the work. Take heed, ye Captains of Industry, and note this truth, that where men and women work together under right influences, much good is accomplished, and the work is pleasurable. Of course there are vinegar-faced philosophers who say that the Scotch custom of pairing young men and maidens in the hayfield is not without its effect on esoterics, also on vital statistics; and I’m willing to admit there may be danger in the scheme. But life is a dangerous business anyway—few indeed get out of it alive!

Burns succeeded in his love-making and succeeded in poetry, but at everything else he was a failure. He failed as a farmer, a father, a friend, in society, as a husband, and in business.

From his twenty-third year his days were passed in sinning and repenting.

Poetry and love-making should be carried on with caution: they form a terrific tax on life’s forces. Most poets die young, not because the gods especially love them, but because life is a bank-account, and to wipe out your balance is to have your checks protested. The excesses of youth are drafts payable at maturity. Chatterton dead at eighteen, Keats at twenty-six, Shelley at thirty-three, Byron at thirty-six, Poe at forty, and Burns at thirty-seven, are the rule. When drafts made by the men mentioned became due, there was no balance to their credit and Charon beckoned.

Most life-insurance companies now ask the applicant this question, “Do you write poetry to excess?” Shakespeare, to be sure, clung to life until he was fifty-three, but this seems to be the limit. Dickens and Thackeray, their candles well burned out, also died under sixty. Of course, I know that Browning, Tennyson, Morris and Bryant lived to a fair old age, but this was on borrowed time, for in the early life of each there was a hiatus of from ten to eighteen years, when the men never wrote a line, nor touched a drop of anything, bravely eschewing all honey from Hymettus. Then the four men last named were all happily married, and married life is favorable to longevity, but not to poetry. As a rule only single men, or those unhappily mated, make love and write poetry. Men happily married make money, cultivate content, and evolve an aldermanic front; but love and poetry are symptoms of unrest. Thus is Emerson’s proposition partially proven, that in life all things are bought and must be paid for with a price—even success and happiness.

Burns once explained to Doctor Moore that the first fine, careless rapture of his song was awakened into being when he was sixteen years old, by “a bonnie sweet sonsie lass” whom we now know as “Handsome Nell.” Her other name to us is vapor, and history is silent as to her life-pilgrimage. Whether she lived to realize that she had first given voice to one of the great singers of earth—of this we are also ignorant. She was one year younger than Burns, and little more than a child when she and Bobby lagged behind the troop of tired haymakers, and walked home, hand in hand, in the gloaming. Here is one of the stanzas addressed to “Handsome Nell”:

“She dresses all so clean and neat,

Both decent and genteel,

And then there’s something in her gait

Makes any dress look weel.”

And how could Nell then ever guess why her cheeks burned scarlet, and why she was so sorry when haying-time was over? She was sweet, innocent, artless, and their love was very natural, tender, innocent. It’s a pity that all loves can not remain in just that idyllic, milkmaid stage, where the girls and boys awaken in the early morning with the birds, and hasten forth barefoot across the dewy fields to find the cows. But love never tarries. Love is progressive; it can not stand still. I have heard of the “passiveness” of woman’s love, but the passive woman is only one who does not love—she merely consents to have affection lavished upon her. When I hear of a passive woman, I always think of the befuddled sailor who once saw one of those dummy dress-frames, all duly clothed in flaming bombazine (I think it was bombazine) in front of a clothing establishment. The sailor, mistaking the dummy for a near and dear lady friend, embraced the wire apparatus and imprinted a resounding smack on the chaste plaster-of-Paris cheek. Meeting the sure-enough lady shortly after, he upbraided her for her cold passivity on the occasion named.

A passive woman—one who consents to be loved—should seek occupation among those worthy firms who warrant a fit in ready-made gowns, or money refunded.

Love is progressive—it hastens onward like the brook hurrying to the sea. They say that love is blind: love may be short-sighted, or inclined to strabismus, or may see things out of their true proportion, magnifying pleasant little ways into seraphic virtues, but love is not really blind—the bandage is never so tight but that it can peep. The only kind of love that is really blind and deaf is Platonic love. Platonic love hasn’t the slightest idea where it is going, and so there are surprises and shocks in store for it. The other kind, with eyes wide open, is better. I know a man who has tried both. Love is progressive. All things that live should progress. To stand still is to retreat, and to retreat is death. Love dies, of course. All things die, or become something else. And often they become something else by dying. Behold the eternal Paradox! The love that evolves into a higher form is the better kind. Nature is intent on evolution, yet of the myriads of spores that cover earth, most of them are doomed to death; and of the countless rays sent out by the sun, the number that fall athwart this planet are infinitesimal. Edward Carpenter calls attention to the fact that disappointed love—that is, love that is “lost”—often affects the individual for the highest good. But the real fact is, nothing is ever lost. Love in its essence is a spiritual emotion, and its office seems to be an interchange of thought and feeling; but often thwarted in its object, it becomes general, transforms itself into sympathy, and embracing a world, goes out to and blesses all mankind.

Very, very rare is the couple that has the sense and poise to allow passion just enough mulberry-leaves, so it will spin a beautiful silken thread, out of which a Jacob’s ladder can be constructed, reaching to the Infinite. Most lovers in the end wear love to a fringe, and there remains no ladder with angels ascending and descending—not even a dream of a ladder. Instead of the silken ladder on which one can mount to Heaven, there is usually a dark, dank road to Nowhere, over which is thrown a package of letters and trinkets, all fastened round with a white ribbon, tied in a lover’s knot. The many loves of Robert Burns all ended in a black jumping-off place, and before he had reached high noon, he tossed over the last bundle of white-ribboned missives and tumbled in after them. The life of Burns is a tragedy, through which are interspersed sparkling scenes of gaiety, as if to retrieve the depth of bitterness that would otherwise be unbearable. Go ask Mary Morison, Highland Mary, Agnes McLehose, Betty Alison, and Jean Armour!

The poems of Robert Burns fall easily into four divisions.

First, those written while he was warmly wooing the object of his affection.

Second, those written after he had won her.

Third, those written when he had failed to win her.

Fourth, those written when he felt it his duty to write, and really had nothing to say.

The first-named were written because he could not help it, and are, for the most part, rarely excellent. They are joyous, rapturous, sprightly, dancing, and filled with references to sky, clouds, trees, fruit, grain, birds and flowers. Birds and flowers, by the way, are peculiarly lovers’ properties. The song and the plumage of birds, and the color and perfume of flowers are all distinctly sex manifestations. Robert Burns sang his songs just as the bird wings and sings, and for the same reason. Sex holds first place in the thought of Nature; and sex in the minds of men and women holds a much larger place than most of us are willing to admit. All religious emotion and all art are born of the sex instinct.

Burns’ poems of the second variety, written after he had won her, are touched with religious emotion, or filled with vain regret and deep remorse, as the case may be, all owing to the quality and kind of success achieved, and the influence of the Dog-Star.

Burns wrote several deeply religious poems. Now, men are very seldom really religious and contrite, except after an excess. Following a debauch a man signs the pledge, vows chastity, writes fervently of asceticism and the need of living in the spirit and not in the senses. Good pictures show best on a dark back-ground. Men talk most about things they do not possess.

“The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” perhaps the most quoted of any of Burns’ poems, is plainly the result of a terrible tip to t’ other side. Bobby had gone so far in the direction of Venusburg that he resolved on getting back, and living thereafter a staid and proper life.

In order to reform you must have an ideal, and the ideal of Burns, on the occasion of having exhausted all capacity for sin, is embodied in the “Saturday Night.” It is all a beautiful dream. The real Scottish cotter is quite another kind of person. The religion of the live cotter is well seasoned with fear, malevolence and absurd dogmatism. The amount of love, patience, excellence and priggishness shown in “The Cotter’s Saturday Night” never existed, except in a poet’s imagination. In stanza Number Ten of that particular poem is a bit of unconscious autobiography that might as well ha’ been omitted; but in letting it stand, Burns was loyal to the thought that surged through his brain.

People who are not scientific in their speech often speak of the birds as being happy. My opinion is that birds are not any more happy than men—probably not as much so. Many birds, like the English sparrow and the blue jay, quarrel all day long. Come to think of it, I believe that man is happier than the birds. He has a sense of remorse, and this suggests reformation, and from the idea of reformation comes the picturing of an ideal. This exercise of the imagination is pleasure, for indeed there is a certain satisfaction in every form of exercise of the faculties. There is a certain pleasure in pain: for pain is never all pain. And sin surely is not wholly bad, if through it we pass into a higher life—the life of the spirit.

Anything is better than the Dead Sea of neutral nothingness, wherein a man merely avoids sin by doing nothing and being nothing. The stirring of the imagination by sorrow for sin, sometimes causes the soul to wing a far-reaching upward flight.

Asceticism is often only a form of sensuality: the man finds satisfaction in overcoming the flesh. And wherever you find asceticism you find potential passion—a smoldering volcano held in check by a devotion to duty; and a gratification is oft found in fidelity.

The moral and religious poems of Burns were written in a desire to work off a fit of depression, and make amends for folly. They are sincere and often very excellent. Great preachers have often been great sinners, and the sermons that have moved men most are often a direct recoil from sin on the part of the preacher. Remorse finds play in preaching repentance. When a man talks much about a virtue, be sure that he is clutching for it. Temperance fanatics are men with a taste for strong drink, trying hard to keep sober. The moral and religious poems of Robert Burns are not equal to his love-songs. The love-songs are free, natural, untrammeled and unrestrained; while his religious poems have a vein of rotten warp running through them in the way of affectation and pretense. From this I infer that sin is natural, and remorse partially so. In Burns’ moral poems the author tries to win back the favor of respectable people, which he had forfeited. In them there is a violence of direction; and all violence of direction—all endeavors to please and placate certain people—is fatal to an artist. You must work to please only yourself.

Work to please yourself and you develop and strengthen the artistic conscience. Cling to that and it shall be your mentor in times of doubt: you need no other. There are writers who would scorn to write a muddy line, and would hate themselves for a year and a day should they dilute their honest thought with the platitudes of the fear-ridden. Be yourself and speak your mind today, though it contradict all you have said before. And above all, in art, work to please yourself—that Other Self that stands over and behind you, looking over your shoulder, watching your every act, word and deed—knowing your every thought. Michelangelo would not paint a picture on order. “I have a critic who is more exacting than you,” said Meissonier—”it is my Other Self.”

Rosa Bonheur painted pictures just to please her Other Self, and never gave a thought to any one else, nor wanted to think of any one else, and having painted to please herself, she made her appeal to the great Common Heart of humanity—the tender, the noble, the receptive, the earnest, the sympathetic, the lovable. That is why Rosa Bonheur stands first among women artists of all time: she worked to please her Other Self.

That is the reason Rembrandt, who lived at the same time Shakespeare lived, is today without a rival in portraiture. He had the courage to make an enemy. When at work he never thought of any one but his Other Self, and so he infused soul into every canvas. The limpid eyes look down into yours from the walls and tell of love, pity, earnestness and deep sincerity. Man, like Deity, creates in his own image, and when he portrays some one else, he pictures himself, too—this provided his work is Art. If it is but an imitation of something seen somewhere, or done by some one else, to please a patron with money, no breath of life has been breathed into its nostrils, and it is nothing, save possibly dead perfection—no more.

Is it easy to please your Other Self? Try it for a day. Begin tomorrow morning and say: “This day I will live as becomes a man. I will be filled with good-cheer and courage. I will do what is right; I will work for the highest; I will put soul into every hand-grasp, every smile, every expression—into all my work. I will live to satisfy my Other Self.”

Do you think it is easy? Try it for a day.

Robert Burns wrote some deathless lines—lines written out of the freshness of his heart, simply to please himself, with no furtive eye on Dumfries, Edinburgh, the Kirk, or the Unco Guid of Ayrshire; and these are the lines that have given him his place in the world of letters.

The other day I was made glad by finding that John Burroughs, Poet and Prophet, says that the male thrush sings to please himself, out of pure delight; and pleasing himself, he pleases his mate. “The female,” says Burroughs, “is always pleased with a male that is pleased with himself.”

The various controversial poems (granting for argument’s sake that controversy is poetic) were written when Burns was smarting under the sense of defeat. These show a sharp insight into the heart of things, and a lively wit, but are not sufficient foundation on which to build a reputation. Ali Baba can do as well. Considering the fact that twice as many people make pilgrimages to the grave of Burns as visit the dust of Shakespeare, and that his poems are on the shelves of every library, his name now needs no defense. The ores are very seldom found pure, and if even the work of Deity is composite, why should we be surprised that man, His creature, should express himself in a varying scale of excellence!

There was nothing of Jack Falstaff about Francis Schlatter, whose whitened bones were found amid the alkali dust of the desert, a few years ago—dead in an endeavor to do without meat and drink for forty days.

Schlatter purported, and believed, that he was the reincarnation of the Messiah. Letters were sent to him, addressed simply, “Jesus Christ, Denver, Colorado,” and he walked up to the General-Delivery window and asked for them with a confidence, we are told, that relieved the postmaster of a grave responsibility.

Schlatter was no mere ordinary pretender, working on the superstitions of shallow-pated people. He lived up to his belief—took no money, avoided notoriety when he could; and the proof of his sincerity lies in the fact that he died a victim to it.

Herbert Spencer has said all about the Messianic Instinct that there is to say, save this—the Messianic Instinct first had its germ in the heart of a woman. Every woman dreams of the coming of the Ideal Man—the man who will give her protection, even to giving up his life for her, and vouchsafe peace to her soul. I am told by a noted Bishop of the Catholic Church that many women who become nuns are prompted to take their vows solely through the occasion of an unrequited love. They become the bride of the Church and find their highest joy in following the will of Christ. He is their only Spouse and Master.

The terms of endearment one hears at prayer-meetings, “Blessed Jesus,” “Dear Jesus,” “Loving Jesus,” “Elder Brother,” “Patient, gentle Jesus,” etc., were first used by women in an ecstasy of religious transport. And the thought of Jesus as a loving, “personal Savior,” would die from the face of the earth did not women keep it alive. The religious nature and the sex nature are closely akin: no psychologist can tell where the one ends and the other begins.

There may be wooden women in the world, and of these I will not speak, but every strong, pulsing, feeling, thinking woman goes through life, seeking the Ideal Man. Whether she is married or single, rich or poor, old or young, every new man she meets is interesting to her, because she feels in some mysterious way that possibly he is the One.

Of course, I know that every good man, too, seeks the Ideal Woman—but that deserves another chapter.

The only woman in whose heart there is not the live, warm, Messianic Instinct is the wooden woman, and the one who believes she has already found him. But this latter is holding an illusion that soon vanishes with possession.

That pale, low-voiced, gentle and insane man, Francis Schlatter, was followed at times by troops of women. These women believed in him and loved him—in different ways, of course, and with passion varying according to temperament and the domestic environment already existing. To love deeply is a matter of propinquity and opportunity.

One woman, whom “The Healer” had cured of a lingering disease, loved this man with a wild, mad, absorbing passion. Chance gave her the opportunity. He came to her house, cold, hungry, homeless, sick. She fed him, warmed him, looked into his liquid eyes, sat at his feet and listened to his voice. She loved him—and partook of his every mental delusion.

This woman now waits and watches in her mountain home for his return. She knows the coyotes and buzzards picked the scant flesh from his starved frame, but she says: “He promised he would come back to me, and he will. I am waiting for him here.”

This woman writes me long letters from her solitude, telling me of her hopes and plans. Just why all the cranks in the United States should write me letters, I do not know, but they do—perhaps there is a sort o’ fellow-feeling. This woman may write letters to others, just as she does to me. Of this I do not know, but surely I would not thus make public the heart-tragedy told me in a private letter, were it not that the woman herself has printed a pamphlet, setting forth her faith and veiling only those things into which it is not our right to pry.

This Mary Magdalene believes her lover was the Chosen Son of God, and that the Father will reclothe the Son in a new garment of flesh and send him back to his beloved. So she watches and waits, and dresses herself to receive him, and at night places a lighted lantern in the window to guide the way.

She watches and waits.

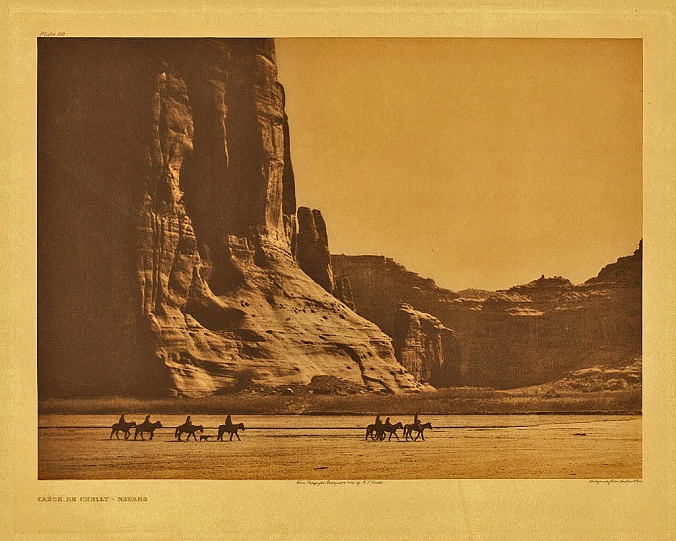

Other women wait for footsteps that will never come, and listen for a voice that will never be heard. All round the world there is a sisterhood of such. Some, being wise, lose themselves in loving service to others—in useful work. But this woman, out in the wilds of New Mexico, hugs her sorrow to her heart, and feeds her passion by recounting it, and watches away the leaden hours, crying aloud to all who will listen: “He is not dead—he is not dead! he will come back to me! He promised it—he will come back to me! This long, dreary waiting is only a test of my loyalty and love! I will be patient, for he will come back to me! He will come back to me!”

This world would be a sorry place if most men conducted their lives on the Robert Burns plan. Burns was affectionate, tender, generous and kind; but he was not wise. He never saw the future, nor did he know that life is a sequence, and that if you do this, it is pretty sure to lead to that. His loves were largely of the earth.

Excess was a part of his wayward, undisciplined nature; and that constant tendency to put an enemy in his mouth to steal away his brains, bound him at last, hand and foot. His old age could never have been frosty, but kindly—it would have been babbling, irritable, senile, sickening. Death was kind and reaped him young. Sex was the rock on which Robert Burns split. He seemed to regard pleasure-seeking as the prime end of life, and in this he was not so very far removed from the prevalent “civilized” society notion of marriage. But it is a phantasmal idea, and makes a mock of marriage, serving the satirist his excuse.

To a great degree the race is yet barbaric, and as a people we fail utterly to touch the hem of the garment of Divinity. We have been mired in the superstition that sex is unclean, and therefore honesty and free expression in love matters have been tabued.

But the day will yet dawn when we will see that it takes two to generate thought; that there is the male man and the female man, and only where these two walk together hand in hand is there a perfect sanity and a perfect physical, moral and spiritual health.

We reach infinity through the love of one, and loving this one, we are in love with all. And this condition of mutual sympathy, trust, reverence, forbearance and gentleness that can exist between a man and a woman, gives the only hint of Heaven that mortals ever know. From the love of man for woman we guess the love of God, just as the scientist from a single bone constructs the skeleton—aye! and then clothes it with a complete garment.

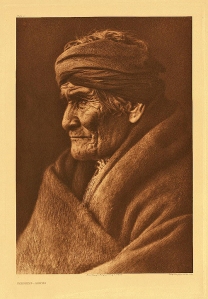

In their love-affairs women are seldom wise, or men just. How should we expect them to be when but yesterday woman was a chattel and man a slave-owner? Woman won by diplomacy—that is to say, by trickery and untruth, and man had his way through force, and neither is quite willing to disarm. An amalgamated personality is the rare exception, because neither Church, State nor Society yet fully recognizes the fact that spiritual comradeship and the marriage of the mind constitute the only Divine mating. Doctor Blacklock once said that Robert Burns had eyes like the Christ. Women who looked into those wide-open, generous orbs lost their hearts in the liquid depths.

In the natures of Robert Burns and Francis Schlatter there was little in common; but their experiences were alike in this: they were beloved by women. Behind him Burns left a train of weeping women—a trail of broken hearts. And I can never think of him except as a mere youth—”Bobby Burns”—one who never came into man’s estate. In all his love-making he never seemed really to benefit any woman, nor did he avail himself of the many mental and spiritual excellencies of woman’s nature, absorbing them into his own. He only played a devil’s tattoo upon her emotions.

If Burns knew anything of the beauty and inspiration of a high and holy friendship between a thinking man and a thinking woman, with mutual aims, ideals and ambitions, he never disclosed it. The love of a man for a maid, or a maid for a man, can never last, unless these two mutually love a third something. Then, as they are traveling the same way, they may move forward hand in hand, mutually sustained. The marriage of the mind is the only compact that endures. I love you because you love the things that I love. That man alone is great who utilizes the blessings that God provides; and of these blessings no gift equals the gentle, trusting companionship of a good woman.

So, having written thus far, I find that already I have reached the limit of my allotted space.

In closing, it may not be amiss for me to state that Robert Burns was an Irish poet whose parents happened to be Scotch. He was born in Ayrshire in Seventeen Hundred Fifty-nine. He died in Seventeen Hundred Ninety-six, and was buried at Dumfries by the “gentleman volunteers,” in spite of his last solemn words—”Don’t let the Awkward Squad fire over my grave!”

His mother survived him thirty-eight years, passing out in Eighteen Hundred Thirty-four. Burns left four sons, each of whom was often pointed out as the son of his father—but none of them was.

This is all I think of, at present, concerning Robert Burns.

he hell starts a serious reflection on critical theory with a quote from a Mel Gibson movie? Why, that would be me! Read on, if you dare:

he hell starts a serious reflection on critical theory with a quote from a Mel Gibson movie? Why, that would be me! Read on, if you dare: